Hi there, and thanks for reading - I’m Ed Gillett, an author and journalist focusing on the points where politics, policing, communities and culture meet.

My first book, Party Lines, comes out in August. From the illicit reggae blues dances and acid-rock free festivals of the 1970s, through the ecstasy-fuelled Second Summer of Love in 1988, to the increasingly corporate dance music culture of the 21st century, Party Lines is a groundbreaking new history of UK dance music, exploring its pivotal role in the social, political and economic shifts on which modern Britain has been built.

In the lead-up to the book’s release, I’ll be sharing some of the fascinating material I’ve uncovered during the writing process, from weird rave ephemera to extended interviews with people who’ve been instrumental in the social and political evolution of UK dance music over the decades.

First up, an apology: it’s been ages since the last edition of this newsletter. There are a couple of reasons for that, from the mundane (I’ve recently started a new job) to the very exciting, like sending out proof copies of Party Lines and making final corrections to the text ahead of its hardback release.

That’s included finalising the cover, which you can now see in all its glory above: a shot of two star-crossed ravers sharing a final moment together after the party’s been locked off (and possibly just before getting arrested).

I think my favourite thing about this photo, aside from its intimacy and strangeness, is how it feels like it could come from any one of several points in recent British history. Rather than dating from the Battle of the Beanfield in the 80s or Castlemorton in the 90s, as I initially assumed, it’s actually from a lockdown rave in Wales in 2020: a neat encapsulation of the overlaps between different eras of anti-establishment pleasure-seeking.

In addition to sorting out the cover, Party Lines’ publication date is now set for 3rd August, with a launch party the same evening in London (more details on that to follow very soon).

You can also now pre-order a copy from places other than Amazon, so please do get on that if you’re so inclined!

A brief history of 🙂

Where the first chapter of Party Lines looks at blues dances and Black soundsystems in the 1970s and 80s as the foundation on which UK dance music was built, the second takes a similar approach to free rock festivals from Windsor to Stonehenge, and later the new Traveller movement.

The earnest peace-and-love rhetoric of the free festivals, and their lineups of protest folk and prog-influenced space-rock noodling, might initially feel a million miles away from acid house’s hedonistic futureshock. But dig a little deeper, and you can find plenty of shared social, political and cultural DNA between these two eras. Both are designed, ultimately, around some concept of ‘British Tribal Music’ to borrow a Hawkwind song title: the soundtrack for thousands of freaks and drop-outs to gather illicitly in some remote corner of the British countryside, and lose their minds together.

That connection is encapsulated in a symbol used by hippies and ravers alike: the yellow smiley face. Unusually for an image so heavily associated with notions of counterculture, the smiley as we know it today is generally understood to have been a corporate invention, most often credited to a US insurance company’s 1963 campaign to “increase staff morale after a series of mergers and acquisitions.”

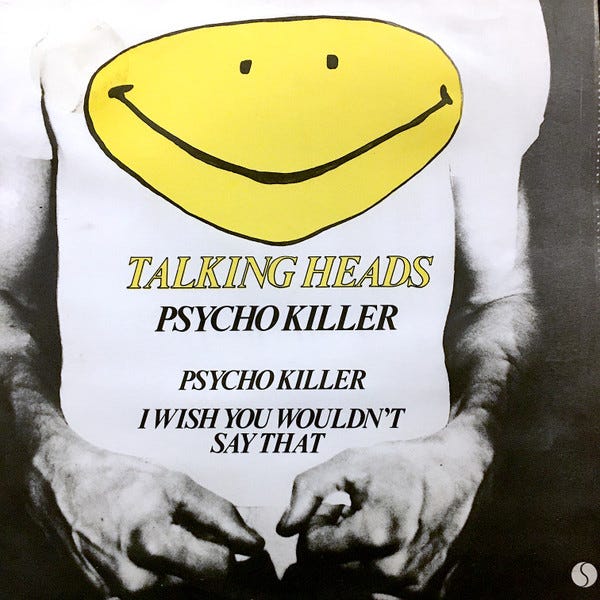

A few years later the image - which wasn’t copyrighted - spilled out into popular culture in a process we’d now surely understand as “going viral”. From a US-wide merchandising fad in the early 70s, with sales of smiley t-shirts and keyrings catering to demand for quick ‘n’ easy feelgood vibes in the wake of Vietnam and Altamont, the smiley appeared on the cover of Mad Magazine in 1972, on Talking Heads record sleeves by the end of the decade, and in Alan Moore’s Watchmen comics by the mid-80s, rapidly embedding itself at the heart of global pop culture.

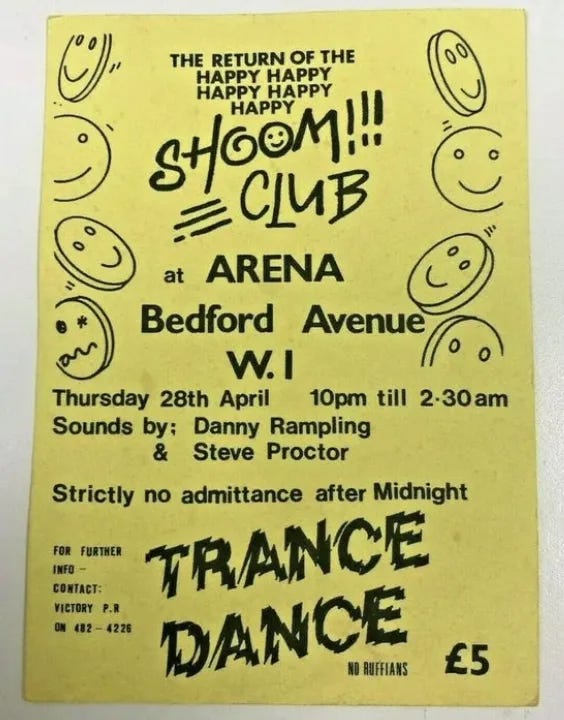

From there, the story of the smiley face tends to jump forward to 1988 and the launch of early South London acid house club Shoom, or Bomb The Bass’ cut-and-paste UK house track Beat Dis, released later that year, whose cover features the same bloodstained yellow grin as Watchmen. From there, the smiley quickly became ubiquitous within UK dance music, plastered across posters, record covers and merchandise alike.

“When you saw someone in a Smiley t-shirt you knew exactly what you were getting,” Terry Farley told Red Bull Music Academy in 2011. “It signified acid house and everything that went with it.”

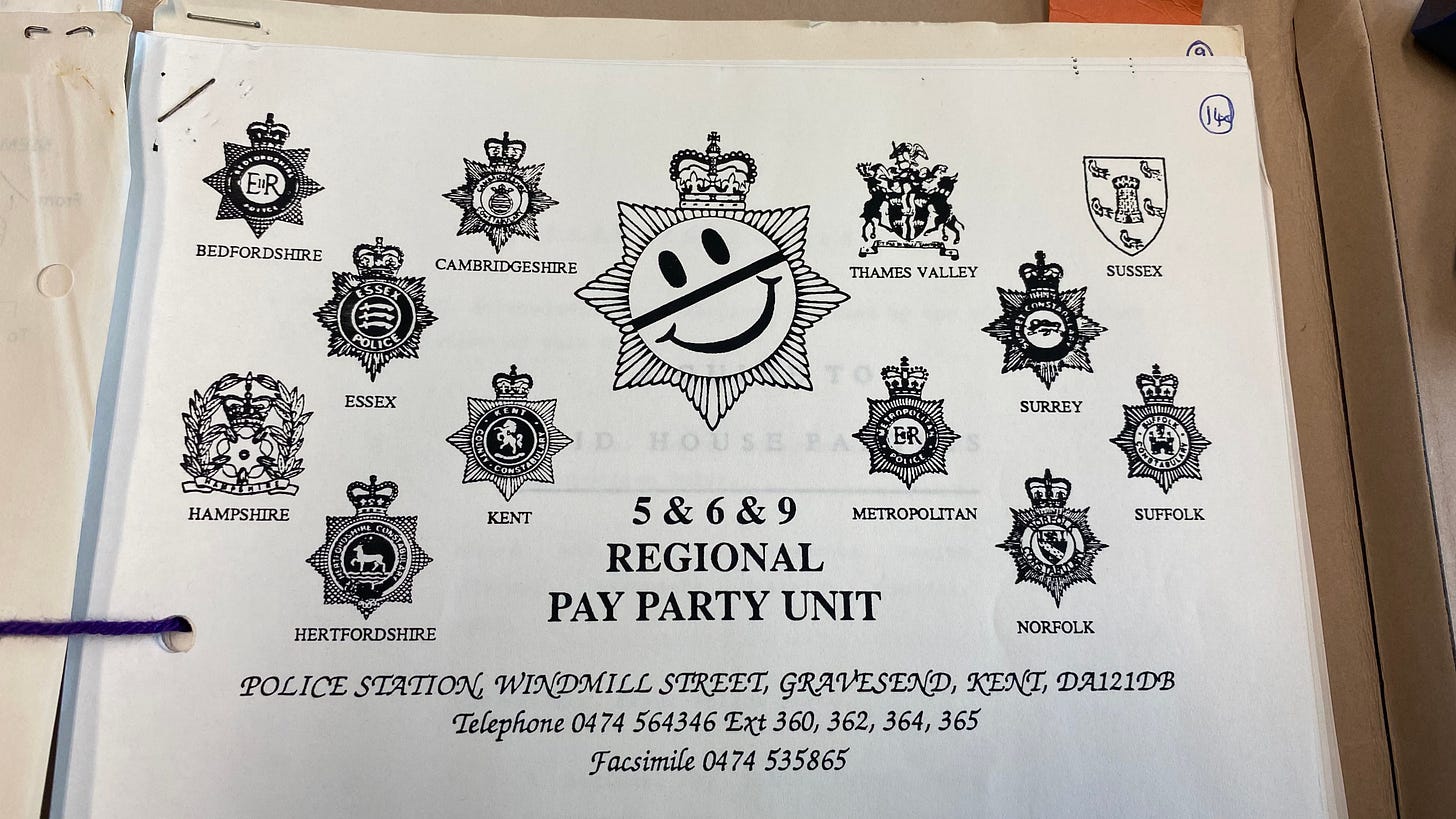

Even the cops got in on the act: one of my favourite archive finds when writing Party Lines was this unofficial logo produced by the Pay Party Unit, the anti-rave police squad set up in 1989, included in a confidential memo to the Home Office and retained in the National Archives:

But there’s another link between the smiley’s US origins and its co-option by the nascent UK rave scene which doesn’t always get mentioned: its prevalence within specifically British hippie circles, and in particular at UK free festivals across the 1970s and 1980s, events which many of the people who’d go on to play formative roles in acid house and rave would have attended as teenagers (Mark Harrison from Spiral Tribe, for example, cites them as a particular influence).

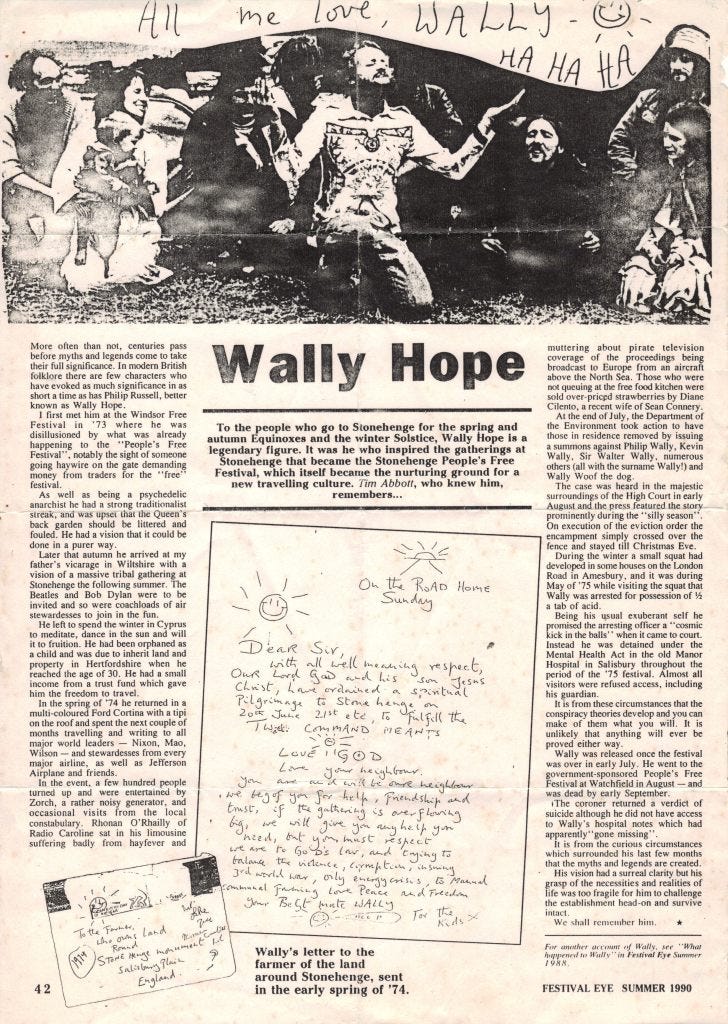

I first spotted this in a letter written by Wally Hope, the so-called Last Of The Hippies, ahead of leading an intended ‘pilgrimage’ to Stonehenge for a rock festival in the summer of 1974. He writes to a local landowner:

Dear Sir,

With all well meaning respect, our LORD GOD and his son Jesus Christ, have ordained a spiritual pilgrimage to Stonehenge on 20th June, 21st etc to fulfill the TWO COMMAND MEANTS:

LOVE GOD

Love your neighbour

You are and will be our neighbour. We beg of you for help, friendship and trust, if the gathering is overflowing big, we will give you any help you need, but you must respect we are to GOD’s law, and trying to balance the violence, corruption, ensuing 3rd world war, oily energy crisis, to manual farming love Peace and Freedom.

Your best mate WALLY

For the Kids x

At the top and bottom of the text sit two smiley faces, one grinning from the centre of a beaming sun, the other free-floating next to Hope’s signature.

Hope’s a fascinating, strange, often hilarious and ultimately tragic figure, covered more extensively in Party Lines: his encouragement of a festival at Stonehenge was rooted in cosmic providence, British folk history and neolithic rituals, but it also had a more direct precedent in the form of the Windsor Free Festival.

Essentially a Home Counties version of Woodstock, Windsor had grown from inauspicious beginnings in 1972, with a couple of bedraggled hippies chanting “give us freedom!” and bands refusing to show up on the basis they weren’t being paid, to tens of thousands of people partying on Crown land within earshot of Windsor Castle by 1974. The same year, a violent police clampdown on the gathering saw the crowds, led in part by Hope, relocate en masse to Stonehenge.

Windsor was also notable for making extensive use of the smiley, bringing it across from the US before its adoption by the Talking Heads and Alan Moores of the world. It seems reasonable to assume that at least some of its subsequent embrace by what would become UK dance music reflects its roots in the UK free party counterculture which immediately preceded it.

But the smiley is a slippery thing: its blank face and context-free positivity makes it easily adoptable by pretty much anyone, and the flow of influence and association around it harder to track. Danny Rampling of Shoom would credit their dalliance with the image to designer Barnzley Armitage, who in turn said he’d copied it directly from America. “I was into all this 70s rare groove stuff [in about ’86],” he told RBMA “so I thought I’d do something 70s American and printed up all these Smiley t-shirts that me and Tim Simenon used to wear.”

Since its rave-related heyday, that same ambiguity has seen the smiley adopted by everyone from US supermarket behemoth Wal-Mart to Covid-era anti-mask group #SmilesMatter (circling back, in doing so, to the latterday Rampling’s own lockdown scepticism).

Either way, while it might be impossible to conclusively establish the precise chain of events which led to the smiley becoming indelibly associated with UK dance music, its appearance in the free festival scene of the 1970s reflects one of the major themes of Party Lines’ early chapters: that the political struggles, societal shifts and cultural upheavals of rave’s supposed golden years weren’t necessarily unique, despite acid house often being presented exploding into life without warning or precedent in 1988.

In fact, UK dance music and the frictions it contains are interesting precisely because they embody and refract deeper narratives threaded through our collective history, from the distant past to the present day: pull on the thread of a smiley t-shirt on the dancefloor at Shoom, and a whole other story unravels itself.

Thanks for reading, and please do spread the word if you’re enjoying these mailouts! Look out for the next installment coming soon (certainly much sooner than the last few).

Cheers,

Ed.