Hi there, and thanks for reading - I’m Ed Gillett, an author and journalist focusing on the points where politics, policing, communities and culture meet.

My first book, Party Lines, comes out in August. From the illicit reggae blues dances and acid-rock free festivals of the 1970s, through the ecstasy-fuelled Second Summer of Love in 1988, to the increasingly corporate dance music culture of the 21st century, Party Lines is a groundbreaking new history of UK dance music, exploring its pivotal role in the social, political and economic shifts on which modern Britain has been built.

In the lead-up to the book’s release, I’ll be sharing some of the fascinating material I’ve uncovered during the writing process, from weird rave ephemera to extended interviews with people who’ve been instrumental in the social and political evolution of UK dance music over the decades.

In the first edition of this newsletter I spoke to Mykaell Riley, whose insight into and experience of Afro-diasporic British music over the last four decades, from his role in 80s reggae band Steel Pulse to his current work as an academic, offers a unique perspective on how power structures have shaped the forms taken by underground UK music.

In this second part of our conversation - edited, like the first, for length and clarity - we discuss his first-hand experiences of the music industry, and the policing of Black dancefloors from the 1970s onwards, and the racial politics of British music all the way back to the court of Henry VIII.

We’ve been talking in the abstract about about cultural appropriation and the simplified narratives which can form around dance music, Mykaell, but I’m interested to know whether you’ve experienced that directly as a researcher or academic?

Sure. Part of what I’ve been looking at recently is the cumulative perspective of what British popular music is, who’s principal to that, and how that plays out internationally.

I can give you a simple example: I’m currently working on a project with a major US museum, which is doing a whole history of African American music, from slavery to where we are now; they also sought to include the Afro-Caribbean impact on American music within that. But they’ve commented that this was challenged by Americans, perhaps not surprisingly, because the general perception across America - both Black and white - is that genres like hip-hop are just American, born out of America.

So part of my job with this project has been to support the museum and challenge this mindset where people in America don’t generally know the whole story: we need to look at the historical impact of Afro-Caribbeans on African American music, and the fact that hip-hop comes directly out of soundsystem culture, that some of the most successful, enterprising and influential figures in early hip-hop are from African Caribbean communities.

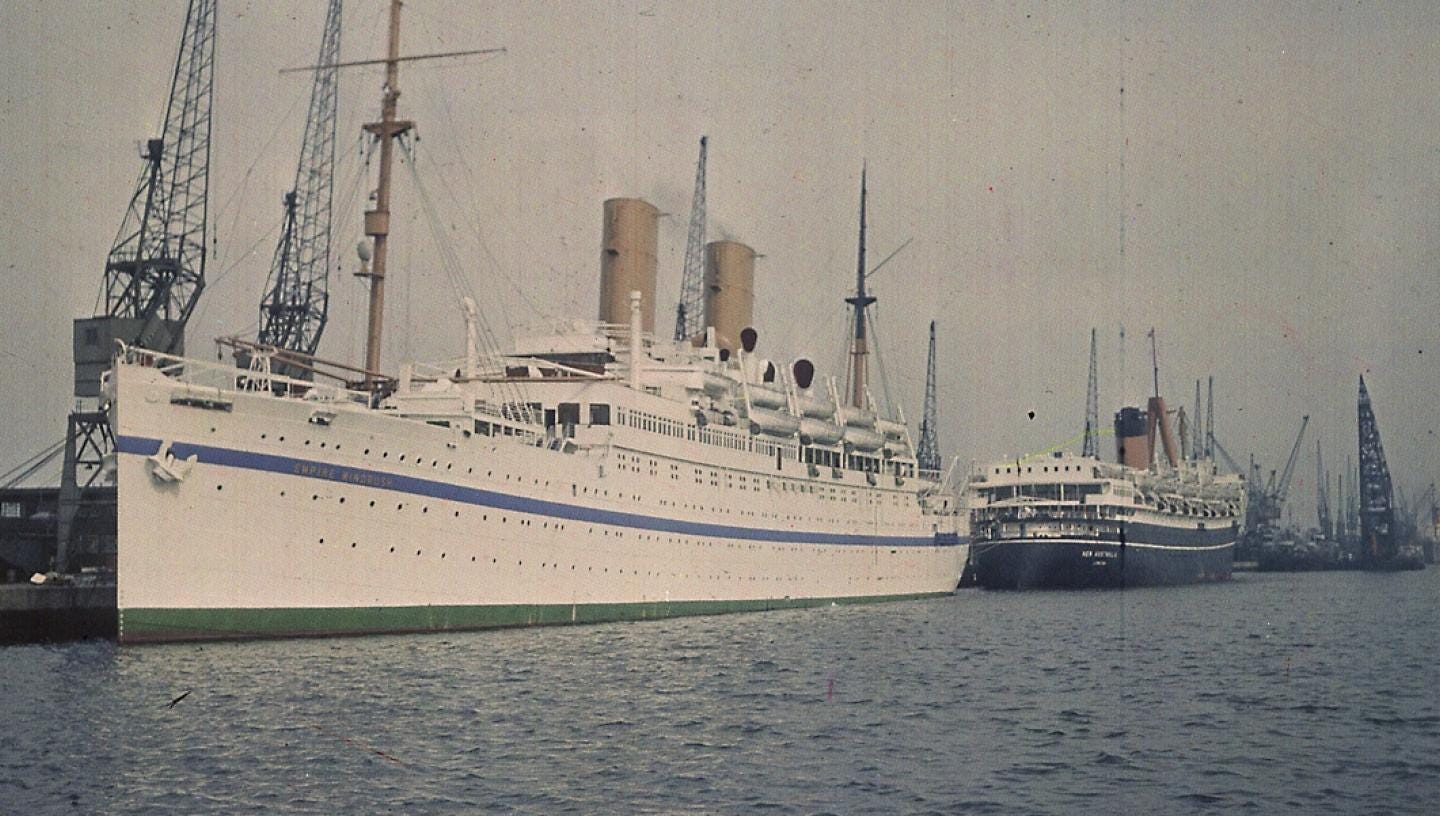

But then there’s also a relationship to the UK which is written out of that story. We don’t exist at all in the popular narrative, when actually when you think about the timeline, the cultural connections between Britain, America and the Caribbean are critical. As you come forward through the decades, post-World War II or the Windrush period, that’s when Caribbeans migrated to America and Europe, often with family members split across both locations. It’s a period when the UK’s role as the main international outlet for Jamaican music helped build the international profile gained by blue beat in the 1950s, ska in the 60s, or the emergence later in the 60s of white pop-reggae artists from The Police to Boy George to UB40. That mutual influence is always there, and feeds into the creation of genres considered exclusively American, but it’s never really been credited.

And if you think about how hip-hop’s evolved since its creation, the UK also influenced how it sounded in the 90s, with artists like Goldie or Soul II Soul, and genres like drum n bass. American pop music has always been primarily produced for the radio, but in the UK we’ve always produced from a Caribbean perspective, for sound systems, for large speakers, which transformed the sound of dance music. In the 90s, that bass-heavy approach becomes more prominent in US productions too. We changed that sonic experience from a production perspective, but it was never credited to the Caribbean community in the UK or elsewhere.

The same’s true of reggae and other African Caribbean music in previous decades: look at Trojan Records and Island Records in the late 60s and early 70s. As that music starts being produced in the UK for an international audience, and the UK becomes the international capital for Caribbean music, the sound changes, producers start adding string sections and orchestration for a European audience. That relationship changed how the music was produced and promoted - obviously in the UK, but also in the Caribbean.

And that process feeds into dance music as well.

Absolutely. When you think about rave culture, particularly the aspects of it which take place outdoors, it’s heavily influenced, by Jamaican music and soundsystem culture that’s where Jamaican music starts too. They’re both about an experience of dancing, but it’s soundsystems which first placed emphasis on amplified music produced for consumption in the open air. But that’s not often credited or acknowledged either.

So again, it’s those less obvious connections which get missed or overlooked. And I’d argue that it’s these kinds of disconnections which feed into a sense of ownership - the idea of how it all happened and who it belongs to - which are usually articulated in the UK by a predominantly white public, and should be challenged.

I agree. I’m interested in your earlier personal experiences of that process, first as a fan of music growing up, and then as a musician: is that sense of disconnection is something you’ve always felt?

So if you go back to the 70s, I grew up in Birmingham, and we all knew that we didn’t have access to the clubs in central Birmingham, that there was a door policy across the clubs which prohibited Black men. They’d let a few Black women in, for the gaze of white men, but Black men were broadly not permitted. And that wasn’t just a one-off, that was the unwritten policy at board level: the people who owned the buildings, owned the clubs, made it clear to the managers of their venues that didn’t want Black men in there.

That meant that, immediately, you had to develop your own space to share and engage with your music. But it also meant that you focused inwards, on your community, and reassessed the principal audience for the music you were making: it was about appealing to the Black community first. That applied to the sounds in the production as well as the lyrics: it was about responding to that that shared sense of restriction, which came from the state, but which politicised what you were doing lyrically and sonically. If you look at the 60s into the 70s, and even into the early 1980s, politicised lyrics were popular, were the norm, were being bought by a wide audience, and acted as a direct insight into the experience of the musicians making that music. The music was sufficiently infectious that you wanted to engage with it, but it also gave you an idea of the challenges facing Black musicians, and by extension Black people, in the 1970s. It wasn’t that we started out wanting to be political, we just wanted wanted to reflect our experience, and that was our experience as a community.

Once Steel Pulse became more popular and transcended our local community, our audience started to include white punks - or at least white youth, let’s put it that way - who were also disgruntled with the political system. They liked the music, but they didn’t understand who we were as a community, our history, our relationship to the idea of Britain, because that wasn’t part of their education. So it meant something different to them.

You can look at soundsystem culture taking off in the mid 70s; by the end of the decade there were something like 500 soundsystems across the UK, working every single weekend, and for the fortunate ones in the week as well. That was the popularity of an underground scene which remained underground because the state positioned it there. By the 80s, the largest audience for that music was white: it’s overlooked, throughout this narrative, that there’s been a consistent embrace by the white community. We also overlook that that one of the biggest audiences for Black music in this country has always been amongst Asian communities, who were a hidden community of colour buying the music, but didn’t necessarily want to deal with the inevitable heavy-handed policing at Black music events.

You can first see all of this come to light in terms of scale with “My Boy Lollipop” in 1964, which hit number 2 and stayed in the charts for five weeks. It was a clear demonstration that the British public had bought into this music, regardless of what the media or the state or other power structures wanted them to believe. And that sets the relationship that we have today.

When you look at the charts, we know that if you were a Black label in the 70s or 80s, even through to the 90s, the charts didn’t reflect your sales. The records shops which were used to collate the charts were supposed to be unbiased and secret to everyone but the BPI, but of course most record companies knew where they were, and sent agents out to buy the records each week. And if you weren’t paying into the BPI then your records weren’t counted at all. So the idea that this music was “underground” the whole time is just a lie, at least in terms of numbers. This was popular British music, born out of British communities: it’s the soundtrack to multicultural Britain in the second half of the twentieth century in the UK, but it’s rarely credited as such.

Then by the time you get into the 90s and the 2000s, you have a generation who grew up with that music in the 70s and 80s, but you also have their kids, who’ve grown up surrounded by that culture and are now making their own music: they know about policing, they know about the record industry, they know about radio. And when you arrive at groups like So Solid Crew, it’s that younger generation saying: “You know what, fuck the state, this is what we want to do. Regardless of what you try and do, we’re going to demonstrate that this is popular music.”

And then, of course, that gets met with the same reaction from the state and other parts of the political establishment as the pressures you experienced as a teenager back in the 60s and 70s.

Absolutely. I initiated something called the Grime Report in 2018, which was the first really big data report on the genre. I was contacted by Live Nation and Ticketmaster, who were looking at challenging the idea of bringing in expensive Black American artists to headline Black British music festivals; they asked if I could help them look at how the public views Black British music, and see whether an event like Wireless could work as a specifically British event?

So I ended up interviewing loads of people and collating lots of data around that. One of the interesting, perhaps lesser-known, components of that report was that I approached the BPI, the Official Charts Company and PRS at the end of 2016 and said - I’m doing this report, would you help, because I need to get some of your data. And no-one said no, exactly, but also no-one was forthcoming with that information, presumably because it had the potential to reveal some of these shortcomings we’ve spoken about.

Another interesting aspect was when I spoke to artists, one section of them said: why do we need to use the term Black at all? This is just British music, right? From a musician’s perspective. They wanted to be accepted as British, because the idea of being part of a specific community or being “underground” didn’t help their sales or their career. But then another section of people said: we don’t care, we’re not waiting for this industry to accept us, because there’s a history here where they’ve constantly sidelined us. And by circumventing the system, we’ve jumped ahead of them: the only thing hampering us now is the police.

And over the year or so that the report was developed, and then published, and people responded, you did see things changing: Black artists being acknowledged more at awards ceremonies, signing major label deals, the system recognising that these artists were popular. But they had to work outside the system to get there, which was also a recognition that no matter how successful you are, the part of the music industry which controls distribution still controls Black music, and your career is inevitably still really fragile. And so we said: how can you be promoting this music in one form, while restricting it for others? White artists were okay, by and large, but Black artists, Black promoters and club owners were all being hampered by the police.

It’s the same cyclical set of activities as decades before: the creative output of the Black community is seized on for a positive narrative by various sections of the media or the industry or the political elite, at the same time as it’s subjected to continued heavy policing and everything else. We could go back six centuries: there was a Black man called John Blanke who was a court musician, he went to Henry VIII in 1531 and said - I’m paraphrasing obviously - look mate, I’m your favourite trumpeter, you’ve got to pay me more, and I want it in writing. He got his wish, and it’s there in the records at Hampton Court, a recognition of the appreciation and value of Black music by the highest in the land.

When we rewind and look where we’re really at, what conversations have been had over the centuries, what progress has been made, we start to understand the parameters we’re working within: so, where music has been used as evidence of how “culturally evolved” the UK is, we should be cautious.